By Jubin Katiraie

As the May 19 Iranian presidential elections drew close, reports continually surfaced of rising levels of political activity on the streets of major cities, which was aimed not at encouraging the election of any candidate but at boycotting the election and declaring the clerical regime as illegitimate. The leading Iranian resistance group, the People’s Mojahedin Organization of Iran, spent several weeks contributing to the public discourse both online and on the ground, with an eye toward demonstrating the lack of serious differences between the supposedly moderate incumbent Hassan Rouhani and his hardline challenger Ebrahim Raisi.

Supporters of the PMOI have hung banners from bridges, painted graffiti, and posted pictures of the group’s leader and president of the National Council of Resistance of Iran, Maryam Rajavi. The slogans displayed on many of those communications declared Raisi to be a “murderer” and Rouhani to be an “imposter,” and they urged a “vote for regime change” in place of either of these non-alternatives.

Raisi’s reputation as a murderer stems from his history as a judge, from which position he condemned hundreds of political prisoners to death. What’s more, Raisi was one of four judges who served on the “death commission” that held trials lasting as little as one minute in the summer of 1988 and swiftly executed approximately 30,000 people who were deemed to harbor disloyalty to the clerical regime.

Meanwhile, the PMOI has been striving to expose Rouhani as an “imposter” because of his predictable failure to live up to the moderate reputation that he claimed for himself during his campaign. That claim was eagerly swallowed by Western executives who were eager to open up the Iranian market to foreign investment. Unfortunately, their eagerness made them inexcusably shortsighted about the risks that would be posed by negotiating and doing business with the Iran.

As a result of narrow focus on a nuclear agreement, much of the West has neglected the 3,000 executions that took place under Rouhani’s term as president, as well as the stepped-up enforcement of vague religious and political laws, which has landed dozens more activists and journalists in jail, along with several persons whose crimes were holding Western citizenship or having significant personal connections to Europe.

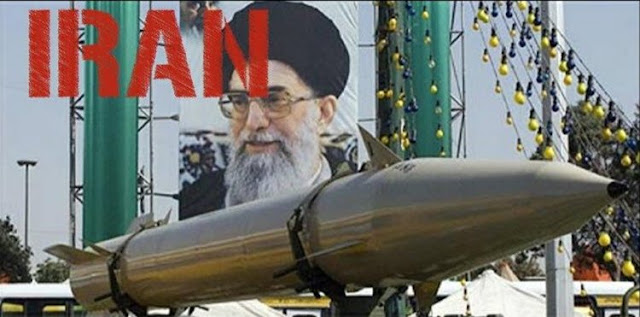

To make matters worse, the crackdown on dissent inside the Islamic Republic has not even corresponded to the anticipated improvement in relations between Iran and the West. Just a few months after the conclusion of nuclear negotiations, the Iranian Revolutionary Guard Corps was testing ballistic missiles in defiance of United Nations Security Council resolutions. Close encounters between Iranian forces and Western naval and commercial vessels have increased dramatically, and their significance has been underscored by extreme rhetoric pouring out of Tehran about readiness for war and the defiance of Western influence.

In light of this, there is both a rational and a moral imperative for Western powers to respond differently to the Iranian puzzle. Rationally, European and American policymakers should understand that an actual change in status of Iran-Western relations was not achievable under Rouhani, and it will not be achievable under any other president, either. Even the most “moderate” president is subordinate to the supreme leader, to whom he must be loyal in order to even qualify as a candidate.

The regime attempts to enforce the same loyalty upon the people as it does upon all candidates for high office. But the activities of PMOI supporters and the non-participation in this election demonstrate that loyalty is absent. The Iranian people’s last attempt at mass defiance of the regime’s will – the 2009 uprisings– was brutally suppressed, with dozens of people being killed and hundreds imprisoned, some of whom are still serving sentences to this day. The collapse of the movement is largely attributable to the lack of support from the international community, and the past four years show that there has been no vindication for it from within the regime.

Only two options were ever possible for this year’s Iranian presidential election: either the continuation of the recent crackdowns and foreign aggression or the worsening of the same. But the millions of Iranians who did not vote and who professed agreement with the PMOI’s campaign point the way to a different option.

The Iranian people have been marginalized in Western policy for far too long. As their political voice, the PMOI and the NCRI have formed alliances with a still-growing array of politicians and public figures throughout the world, but it still remains for them to fully break into mainstream policy circles. Hundreds of international dignitaries converge on Paris each year to attend the NCRI’s annual rally for a free Iran, calling for regime change by the Iranian people, but even more policymakers ought to pay attention to the next event which will be held on July 1st.

By then it will no doubt be clear that there are still no prospects for improvement in the behavior of the Iranian regime. And with that in mind, the NCRI and its supporters will be in a position to explain the domestic support that will have proceeded beyond the boycott campaign. They will be in a position to explain to an even larger and more receptive international audience the ten-point plan that Maryam Rajavi has outlined for the future of the country.

That plan calls for a commitment to secularism and to the free elections that are absent from the country today. It demonstrates unmistakable alignment between the goals of the Iranian resistance and the interests of Western democracies. And in light of the mass boycotts of the polls on May 19, it is a plan that is endorsed by much of the population of Iran. Today, those people are only waiting for a sign that the international community has stopped looking for the best in Iran’s clerical regime and has instead started looking for its end.

Source: Much of the Iranian Public Wants Regime Change and Should be Given Western Support

As the May 19 Iranian presidential elections drew close, reports continually surfaced of rising levels of political activity on the streets of major cities, which was aimed not at encouraging the election of any candidate but at boycotting the election and declaring the clerical regime as illegitimate. The leading Iranian resistance group, the People’s Mojahedin Organization of Iran, spent several weeks contributing to the public discourse both online and on the ground, with an eye toward demonstrating the lack of serious differences between the supposedly moderate incumbent Hassan Rouhani and his hardline challenger Ebrahim Raisi.

Supporters of the PMOI have hung banners from bridges, painted graffiti, and posted pictures of the group’s leader and president of the National Council of Resistance of Iran, Maryam Rajavi. The slogans displayed on many of those communications declared Raisi to be a “murderer” and Rouhani to be an “imposter,” and they urged a “vote for regime change” in place of either of these non-alternatives.

Raisi’s reputation as a murderer stems from his history as a judge, from which position he condemned hundreds of political prisoners to death. What’s more, Raisi was one of four judges who served on the “death commission” that held trials lasting as little as one minute in the summer of 1988 and swiftly executed approximately 30,000 people who were deemed to harbor disloyalty to the clerical regime.

Meanwhile, the PMOI has been striving to expose Rouhani as an “imposter” because of his predictable failure to live up to the moderate reputation that he claimed for himself during his campaign. That claim was eagerly swallowed by Western executives who were eager to open up the Iranian market to foreign investment. Unfortunately, their eagerness made them inexcusably shortsighted about the risks that would be posed by negotiating and doing business with the Iran.

As a result of narrow focus on a nuclear agreement, much of the West has neglected the 3,000 executions that took place under Rouhani’s term as president, as well as the stepped-up enforcement of vague religious and political laws, which has landed dozens more activists and journalists in jail, along with several persons whose crimes were holding Western citizenship or having significant personal connections to Europe.

To make matters worse, the crackdown on dissent inside the Islamic Republic has not even corresponded to the anticipated improvement in relations between Iran and the West. Just a few months after the conclusion of nuclear negotiations, the Iranian Revolutionary Guard Corps was testing ballistic missiles in defiance of United Nations Security Council resolutions. Close encounters between Iranian forces and Western naval and commercial vessels have increased dramatically, and their significance has been underscored by extreme rhetoric pouring out of Tehran about readiness for war and the defiance of Western influence.

In light of this, there is both a rational and a moral imperative for Western powers to respond differently to the Iranian puzzle. Rationally, European and American policymakers should understand that an actual change in status of Iran-Western relations was not achievable under Rouhani, and it will not be achievable under any other president, either. Even the most “moderate” president is subordinate to the supreme leader, to whom he must be loyal in order to even qualify as a candidate.

The regime attempts to enforce the same loyalty upon the people as it does upon all candidates for high office. But the activities of PMOI supporters and the non-participation in this election demonstrate that loyalty is absent. The Iranian people’s last attempt at mass defiance of the regime’s will – the 2009 uprisings– was brutally suppressed, with dozens of people being killed and hundreds imprisoned, some of whom are still serving sentences to this day. The collapse of the movement is largely attributable to the lack of support from the international community, and the past four years show that there has been no vindication for it from within the regime.

Only two options were ever possible for this year’s Iranian presidential election: either the continuation of the recent crackdowns and foreign aggression or the worsening of the same. But the millions of Iranians who did not vote and who professed agreement with the PMOI’s campaign point the way to a different option.

The Iranian people have been marginalized in Western policy for far too long. As their political voice, the PMOI and the NCRI have formed alliances with a still-growing array of politicians and public figures throughout the world, but it still remains for them to fully break into mainstream policy circles. Hundreds of international dignitaries converge on Paris each year to attend the NCRI’s annual rally for a free Iran, calling for regime change by the Iranian people, but even more policymakers ought to pay attention to the next event which will be held on July 1st.

By then it will no doubt be clear that there are still no prospects for improvement in the behavior of the Iranian regime. And with that in mind, the NCRI and its supporters will be in a position to explain the domestic support that will have proceeded beyond the boycott campaign. They will be in a position to explain to an even larger and more receptive international audience the ten-point plan that Maryam Rajavi has outlined for the future of the country.

That plan calls for a commitment to secularism and to the free elections that are absent from the country today. It demonstrates unmistakable alignment between the goals of the Iranian resistance and the interests of Western democracies. And in light of the mass boycotts of the polls on May 19, it is a plan that is endorsed by much of the population of Iran. Today, those people are only waiting for a sign that the international community has stopped looking for the best in Iran’s clerical regime and has instead started looking for its end.

Source: Much of the Iranian Public Wants Regime Change and Should be Given Western Support

Comments

Post a Comment